I would like to start this journey into reality with the idea of consciousness; it’s a word thats used a lot and seems to have a number of meanings, but on this blog I am going to classify it into two parts: one is our experiences of the world around us and all that we can perceive. It is our ability to orient and appreciate the external world through our sacks of blood, organs and brain. The second is our conscious-self; this is what separates me from you and gives us our feeling of self-identity. In this post, I am going to particularly draw attention to the idea of consciousness in the world around us.

It is often assumed that our senses allow us to perceive the world as it actually is, this so-called reality that we choose to bob around in. What it actually comes down to is whether our brains are able to accurately interpret the multitude of inputs it receives all the time. Our brains do not really know what is out there in the world. It does not see light or listen to sounds it merely receives electrical impulses that let it have a good guess at what is going on. What we are perceiving (or perhaps more accurately hallucinating) is just our brains’ interpretation. So how do we know what we hallucinate is correct? Well we don’t; however, when our ‘hallucination’ matches what others say they are perceiving then that’s what we call reality. Most of the time this reality is consistent for everyone, but sometimes these processes can create different outcomes for different people causing us to perceive different things.

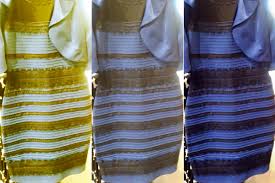

A good example of this is that white/black dress debacle from a few years ago. This particular illusion comes from the idea that we have evolved to see in daylight, which has a range of colours from pinkish-red to blue-white. Now when our brain perceives inputs in the visual cortex it is programmed to subtract the information about the illuminant (that is the wavelengths of light illuminating the world and bouncing off the object) and to find information on the actual reflectance (the proportion of light that is reflected when striking the object). Because daylight has such a wide spectrum of colour the brain may subtract either the blueish colour and thus leave the dress looking white/gold or will subtract the gold-side therefore leaving the dress looking blue/black.

I think it may be best to limit this post to just the processes of visual perception; of course there are whole other systems of auditory and tactile perception that also interpret the world through the inputs they receive, but I think it’s easier to picture the visual process.

So how do we perceive the world? One might assume that the eyes just take perfect snapshots of the world and relay them to the visual cortex where we browse through this chronological slideshow of our lives. In reality our eyes just perceive a sort of 2D shadow world, from which our brain makes predictions on what/where everything is. When we look at the world around us, we absorb spatial patterns of light that bounce off different objects and land on the flat surface of our eye. This two-dimensional map is then sent to the brain where it must construct a three-dimensional image of the world. The problem with this is that many different objects can all cast the same shadow so knowing which one is correct is sometimes a difficultly. There is also the issue that the brain doesn’t have hours to ponder this, it has a fraction of a second. When a ball is thrown at your face there is a rapid and continuous flow of information that has to dealt with, which will be the decider between some safe hands or some broken teeth.

The brain has to deal with these challenges, being constantly bombarded with this plethora of information. It has to be able to process it efficiently to generate an accurate picture of the world. A way it optimises this process is to try and predict what sensory inputs we will receive based on what we have experienced before. We do not simply rely on the input coming into the sensory receptors instead these inputs are combined with our expectations about what we should be perceiving. This is because it is far less strenuous for the brain to create an improvised reality based on educated guesses and using a few simple rules or assumptions.

If you look at the picture, you may be able to make out a street with a car driving along and a pedestrian on the pavement. In actual fact both the car and the pedestrian are the same image, but the pedestrian image is rotated and made smaller. The fact that we see this street as a car and a pedestrian is due to the fact that the visual input is weak or ambiguous and therefore the brain is more likely to rely on prior expectations. The shapes themselves show no information to define them as either car nor object, but the context of the street leads us to perceive them this way.

This idea of prior expectation really affects how we perceive our world and is likely acquired over a lifetime of experience. This theory is an incarnation of the “Bayesian Brain” which proposes this kind of probabilistic inference occurs when our sensory signals (Bottom-up processing) is assessed with our prior knowledge (Top-down processing) about a situation. This model of Bayesian inference uses the method of predictive coding which uses prediction errors to minimise the amount of sensory information the brain receives. A prediction error is the difference between the actual and expected incoming information and can be transmitted to the brain to improve efficiency of signal transmission.

In terms of the actual neurological structures behind how these processes work, fMRI have shown that there may be a feedback from higher to lower level sensory cortices. This feedback is assumed to be these prediction errors and have shown that some neural responses are dampened when the predictions made are confirmed by the input from the sensory systems. These signals are enhanced when the prediction does not match. For example, when you are bothered by a constant sound, such as someone chewing loudly or the incessant whirring of an air-conditioning unit, the noise will at first be distracting. It will bore into your brain leaving you unable to focus on the most basic task until at some point, it will cease to be distracting. This is because the brain is able to predict the sound and dampen it; however, when the noise stops that silence will hang in the air and will be very noticeable for the same reason that our brain expects to be ‘hearing’ it. Another example is why we find it very difficult to tickle our self. The brain can predict the sensory effect of the movement and dull this stimuli.

I feel as though this point of how our expectations shape our reality has been laboured enough by me, so to conclude this post I think it comes down to how we view this term hallucination. If it is a perception of something not present then where do we draw this line between what is present and what we expect to be present? The fact that we can perceive the world through this anticipatory, pre-activated brain, where our expectations seem to drive our reality begs the question of how much is misrepresented in the world around us, and how much of our perception is down to our inherent beliefs about the world?

Here is a link to some Paradoxes/Illusions: https://www.scientificpsychic.com/graphics/index.html

If this has interested you or you have any other ideas, please comment as I would be keen to explore this topic further.

References

Some further reading:

- https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2018/10/hallucinations-hearing-voices-reality-debate/571819/

- https://science.sciencemag.org/content/357/6351/596

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0960982204007250

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00276/full

- http://www.peterkokneurosci.com/My_papers/DeLangeHeilbronKok_TICS2018.pdf

- https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1364661307002550

- http://greymattersjournal.com/code-of-conduct-bayesian-predictive-coding/

- https://aeon.co/essays/how-our-brain-sculpts-experience-in-line-with-our-expectations

- https://ase.tufts.edu/cogstud/dennett/papers/surprisesurprise.pdf